Author: fortyninecubed

#MathsConf17

Yesterday, I attended my third MathsConf in Birmingham – #MathsConf17. As ever, the day was so much fun and is the most excellent CPD – I cannot thank Mark (@EmathsUK) and the whole team at La Salle Education (@LaSalleEd) for the work that they put into organising these events. If you’ve not been to one yet, take a look at the upcoming list of locations and dates and come along! You won’t regret it.

I arrived in Birmingham on Friday night with one of my colleagues, which was an excellent opportunity to catch up with some Maths education Twitter friends. As you may expect, the conversations quickly turned into sharing and solving interesting maths problems and sharing ideas for enrichment lessons. My offering was this excellent area maze puzzle, which certainly caused a few headaches!

On the day itself, after some opening remarks from Mark McCourt and Andrew Taylor (@AQAMaths), including a huge thank-you to the amazing Rob (@RJS2212) for all that he does by selling raffle tickets and organising tuck shop, it was time for speed-dating.

From speed-dating, I took away the following ideas (apologies for lack of credits – completely forgot to write down names):

- When teaching factorising quadratics, atomise the procedures/steps, before bringing it all together. I still don’t do this as effectively as I would like, so it was really interesting to see how someone else had split the process up, and hear their reflections on how it had worked in the classroom.

- I chatted to Ashton (@ashtonC94) about how is now teaching finding Lowest Common Multiple – effectively by finding the product of the numbers in question, and then dividing by the Highest Common Factor. I’ve been aware of this method but never used it before – I’ve generally gone for using Venn diagrams, but given how frequently my students make mistakes with these, I really like this approach. Definitely food for thought!

- I spoke to someone else who shared the retrieval practice grids that he is using with his classes at the moment as starters. I really like the layout of these, and the way that they allow questions to be targeted effectively to the topics that your classes have studied.

Session 1:

After speed-dating, session 1 began! I attended Literacy in Mathematics by Jo Locke (@JoLocke1). I’ve met Jo several times before (and had dinner with her on Friday!), but it was my first time seeing her deliver a session, so I was really looking forward to it. Jo made the point that we are all teachers of literacy, and that students with low levels of literacy will go on to underperform in Maths, if they are not able to access what is being asked of them. This really resonated with me.

It’s also worth pointing out that I teach lots of students who I would describe as having excellent literacy – their spelling and grammar is always impeccable, and they can speak and write eloquently. Even then, I’ve seen students like this fall apart in exams if the word ‘integer’ is used, and I’ve seen similar students look astonished when asked to write down ‘the range of solutions which satisfy an inequality’. Mathematical language needs to be taught clearly and explicitly, and this is something that I have definitely neglected in the past.

Jo shared lots of different resources and strategies to ensure that our students develop the literacy skills that they need. A key takeaway for me was discussing etymology with our students; she made the point that students are frequently really excited to hear about the origins of interesting mathematical words, and so I am going to make more of an effort to do that when teaching. Even aside from student interest, I think it can help to develop their long-term recall of key ideas. If, for example, we explain how algebra is taken from the Arabic meaning ‘the reunion of broken parts’, then this leads into the process of what it actually means to solve an equation.

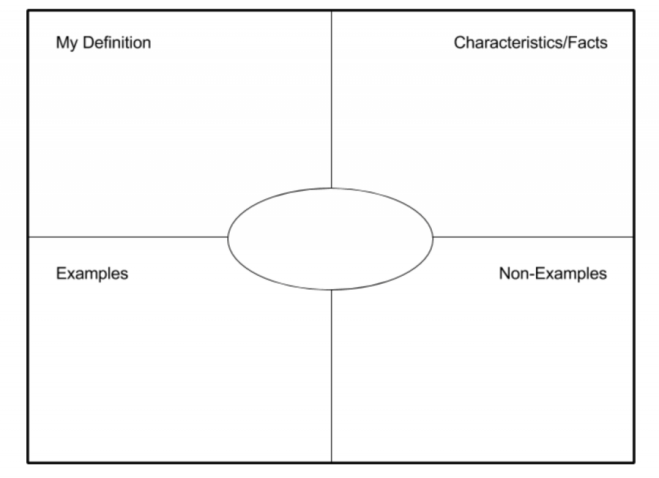

The other idea that Jo shared that I loved and will definitely be using was Frayer models. This is an idea which I feel sure I must have seen at some point before, but have definitely need used in the classroom. The model looks like this, and can be used in various different ways.

I really love the opportunity for students to create their own examples/non-examples: all too frequently, we show our students lots of examples of what a probability is, but never what a probability is not. I think non-examples are incredibly powerful for students to build a fuller understanding of a given concept, and so I am excited to try this out.

Session 2

For session 2, I attended Bernie Westacott’s (@berniewestacott) session on ‘Making Maths Memorable – Progression in Fractions’. Again, this was my first time seeing Bernie speak and I was not disappointed!

Bernie focused on the use of different representations of fractions and how we can use these to support students to acquire a conceptual understanding. We had the opportunity to explore Cusinaire rods, Numicon and Multilink cubes, and build various models to represent various problems. Throughout, Bernie discussed the influence of ‘Singapore Maths’, and how that approach can be used in British classrooms to ensure our pupils can become as successful as possible.

Now, to be completely honest: with the exception of the odd box of multilink cubes, I don’t make use of manipulatives in my classroom. This is partly because we don’t have other equipment, but primarily because I don’t know how to use them effectively! The reason that I found Bernie’s session so useful, in spite of this, is that it gave me a much better insight into what is going on in primary Maths classrooms at the moment, and I think a better understanding of what our students will have been previously exposed to can only improve the quality of teaching and learning.

The other reason that I found it so fascinated was how careful and precise Bernie was with all of his language used throughout. If students are not 100% fluent with the idea that the parts of a fraction must all be equal, then any subsequent teaching is being built on shaky foundations. As such, rather than using the word one half to describe ‘1/2’, Bernie described it consistently as ‘one out of two equal parts of the whole’. ‘2/3’ became ‘two out of three equal parts of the whole’, and so on. This was fascinating, and it has certainly made me think about adding and subtracting fractions and the language that I am using then. We also looked briefly at division, and how it can be interpreted in a number of different ways. Again, this is something that I typically gloss over in the classroom: I am going to make more of an effort to slow down to allow my pupils to explore the nuances which are lost when going at speed.

Session 3

I led a workshop for Session 3 (my solo #MathsConf debut!), entitled ‘Tackling Re-Teaching’. I am not going to speak about it here, because I want to write something about it separately and this could otherwise become unreasonably long. I will just say the hugest of thank-yous to Pete Mattock (@MrMattock) for stepping in and lending me his laptop at the last minute – the crisis was averted thanks to him! Similarly, I cannot thank enough everyone who attended and has spoken to me about it since; I really hope that you all found something in it useful (and thank-you for carrying on listening as my microphone was replaced mid-sentence!). As I say, there will be something written about it which will explain everything in full.

Session 4

I found it incredibly difficult to choose which workshop to attend for session 4! Luckily, I had two colleagues who were also at #MathsConf with me, so the decision was made to split up and to feedback to each other later. I went to Pete Mattock’s session (@MrMattock) on ‘Time to Revisit… Teaching For Mastery’ and I am so glad that I did.

There was so much to take away from Pete’s session that it is hard to know where to begin! He made the point that students who achieve the best outcomes have typically had a mixture of ‘teacher-directed’ instruction and ‘inquiry-based’ methods. Specifically, teacher-directed approaches appear in most/all lessons or learning episodes, and inquiry-based approaches appear in some. Too frequently, it is easy to see Maths education as a series of dichotomies which can be really unhelpful – it was refreshing to see the fact that both approaches have a valuable role to play.

Pete took us through a number of different ways of modelling different mathematical procedures – and made the point that just teaching ‘rules’ is unhelpful. An excellent example he gave was that of BIDMAS: students who are often exposed to BIDMAS are taught it as an arbitrary set of rules that must be followed, but Pete made the point that the correct priority of operations is a mathematical necessity. He supported this with visual representations, which I still need to explore more for myself before showing to students, but which were incredibly powerful.

I also loved the way in which Pete showed the addition and subtraction of negative numbers. I’ll be honest: I have tried teaching adding and subtracting negative numbers in multiple different ways to multiple different classes, but never particularly successfully. I have tried pattern-spotting and analogy and rule-following and number-lines and everything has seemed to collapse at some point, and students revert back to ‘two minuses make a plus’. The model that Pete showed involved modelling negative numbers as vectors: I cannot do justice here to how effective it was, but I will definitely be using it in future. (I will also point out that Pete has a book being published soon – you can order it at: https://www.crownhouse.co.uk/publications/visible-maths), which includes these ideas.

We also looked at the division of fractions using a Cuisinaire rods approach – this is another topic which frequently comes back to rule following (‘keep, flip, change’) and it was so useful to see a model that actually works and provides meaning to the process. Finally, I am so pleased that Pete spoke about ‘exit strategies’. He made the point that our students won’t have access to manipulatives in exams, and that often, drawing diagrams is a more time-consuming approach than being able to answer a question without. Pete modelled how, over time, he will move his students onto a more ‘abstract’ approach, but this has acquired meaning through the multiple representations that students have used on their journey.

Overall, I had the most fantastic day! MathsConfs are such well-run events and there are so many different workshops being offered that you can really tailor the whole day to suit your own personal CPD needs. Thanks so much to everyone who makes the day what it is – see you all in Bristol in March for #MathsConf18!.

Teaching Mixed Attainment Year 7: A year of Mistakes!

At my current school, Year 7 Maths lessons are taught in their tutor groups; they are not placed into sets until Year 8. If you’d asked me six months ago how I felt about this, I’d have responded with something along the lines of ‘it is just so hard’. It really was.

Whenever I taught my Year 7 class last year, I had an overwhelming feeling that many were not progressing as well as they should be. In terms of the assessment system in place at my school, they were generally performing as expected, but I was still not convinced. I felt that strategies that I was using to stretch and challenge the highest attaining pupils were not sufficiently stretching and challenging, and I felt deeply guilty that I wasn’t supporting the lowest attaining pupils to master fundamental concepts. Above all, I was knackered! Despite being a lovely class, it felt that I had so much more to think about compared to teaching other setted classes, and so planning and preparation took significantly more time.

This year, however, I’m feeling quite differently about the whole experience! Obviously, we are only three weeks into term right now, but so far, it seems to be going significantly more smoothly. I will also say this with the caveat that I am not necessarily advocating for teaching mixed attainment classes. I am aware that the research is fairly inconclusive as to which is ‘better’ (especially when considering better for whom and the extent to which this is the case). Nonetheless, I am currently loving teaching Year 7, and so in this post I am going to share three main mistakes I was making last year, as well as the strategies that I’ve put into place to improve things.

Mistake 1: ‘Teacher explanation and modelling must be done quickly.’

The reason I continually made this mistake last year was that I didn’t want my highest attaining pupils to be bored. If, for example, I was teaching pupils how to find the nth term of a linear sequence, I knew that the highest attaining pupils may well be able to do this after seeing one example. As such, I would often talk quickly and at a more superficial level than I would with other classes. Regularly, I would say things along these lines:

‘Okay, so today we’re going to be adding fractions. I know some of you in here will already be quite confident with this, so we’re just going to go through a couple of super quick examples and then you can be moving onto some more challenging questions’.

In short, I was consistently apologetic for having to explain or model or demonstrate.

The consequence of this was typically as follows: while my highest attaining pupils would have understood a given procedure at a superficial level, several would have over-generalised or under-generalised and formed misconceptions, which I often didn’t detect until later. The lowest attaining pupils were often completely overwhelmed by these highly rushed demonstrations, and I would find myself immediately going over to the same few pupils and re-explaining at a more appropriate pace. Over time, this resulted in some pupils tuning out during whole class exposition, as they were aware they were only going to hear it again from me. For all pupils who fell somewhere in the middle of these two groups (a significant proportion), their success would have depended pretty much entirely on how much prior knowledge they already had. I was failing to use effective formative assessment strategies (multiple choice questions, mini whiteboards) because I was so keen to move them on to their differentiated work, which meant I was never really sure until the end of the lesson if they had been successful.

Mistake 2: ‘All independent work must be differentiated into multiple levels.’

In these Year 7 lessons, there would always be ‘bronze, silver and gold’ tasks. Sometimes, in my planning, I would worry that gold wouldn’t be sufficiently challenging, and so would have to introduce the platinum super challenge level. At other times, I would worry that some pupils wouldn’t be able to access the bronze task, so I would spend time creating support sheets to be used alongside.

First of all, this was a nightmare to facilitate. I would spend forever at the photocopier before teaching them, and because I tried not to allocate in advance which level pupils should be working at, I would print multiple spare copies which would end up wasted. It also meant that simple things such as reading out the answers to the first five questions to assess that everyone was on the right track took far longer than necessary. More problematic than this, though, was that pupils often did not understand the task they needed to be doing.

If, for example, the lesson was on adding fractions, the gold or platinum task would often be in the form of a puzzle or investigation from Nrich, or some UKMT problems. Due to the superficial exposition that had happened, pupils didn’t have the core knowledge in place to be able to access these. Equally frustratingly, as it would have taken too much time to detail exactly what was required for each task, pupils may have had the required knowledge but remained unclear about exactly what they were being expected to do.

At the other end of the spectrum, if the lesson was on adding fractions, the bronze or support task may have been something related to adding fractions with the same denominator, and in this case, the examples that I had rushed through to the whole class wouldn’t have helped pupils to complete it. Now, I absolutely still differentiate work for all my classes, but the way that I do this now is quite different (and easier to implement): this will be discussed later.

Mistake 3: ‘Pupils will be working on different skills within the same lesson.’

This mistake, on the surface, appears very similar to the second mistake outlined above. However, this feels that it was an even bigger barrier to being successful when teaching Year 7.

As an example of this: in our Year 7 Scheme of Work, we teach/review the process of multiplying and dividing numbers. Obviously, we are aware that all pupils will have learnt this at primary school and most pupils are reasonably proficient at it in Year 7, but we are also aware that without complete fluency in these topic areas, pupils will struggle with more complex procedures. Now, within my Year 7 class last year, I had pupils who could not recall their times tables, alongside pupils who could demonstrate multiplying three and four digit numbers. Neither point seemed quite appropriate to start, so I began by quickly modelling multiplying two digit numbers before pupils began practising.

For the strongest pupils, I began by giving them some worded problems which required them to multiply large numbers. This was a terrible idea: they didn’t need to think about the context in the problems (they knew) it was just going to be multiplication, so they rushed through and became bored, as is understandable. Quickly, I improvised, and moved them on to practising multiplying and dividing decimals, as this seemed like a fairly natural progression.

However, later in the year, I was required to teach the whole class how to multiply decimals. At this stage, I thought a good next step for the highest attaining pupils who were already fairly fluent would be to look at dividing decimals, and then decided to introduce them to standard form. In effect, throughout the year, I helped the strongest pupils to access lots of topics and replicate lots of procedures, but they were not being given the opportunity to think more deeply about the maths and the concepts involved: it was a case of procedure, procedure, procedure. Meanwhile, I had other pupils struggling to access the primary content of the lesson, and it felt as though pupils were developing the mindset of ‘oh, well, those are the people who are good at maths’: ability was being viewed as fixed.

What next?

At the start of this academic year, I became determined to improve my Year 7 teaching. While I am aware that it wasn’t completely terrible last year (honestly, believe it or not, there were moments of excellence in the midst of all the mistakes), I knew I could be doing a better job.

The first decision I made was to slow down when explaining and modelling. This has not been easy. I have to keep reminding myself that even the very brightest pupils will not be unduly negatively affected if they have to wait an extra five minutes before they begin their own work. Obviously, I am still the person in the classroom who knows the most maths, and so I’m trying to feel less guilty about making sure my explanations are clear and my examples are well chosen. This still does not need to take that long (indeed, by making use of silent teacher and example problem pairs), this is often very efficient. Moreover, when I am talking, I have realised that the prior knowledge my pupils have isn’t what I had presumed it would be.

Just yesterday, for example, I discovered that none of my current class had been shown the divisibility rules for 3 and 9 – it was so joyous when they discovered this was true. If I had rushed through as before (‘right, this is how we divide numbers, I know some of you can do this already, this will be quick’), then that point would have been lost.

I am also developing my AfL strategies with this class so they are far more effective than before. This is so important with mixed classes; all too frequently you will find a student who excels at a particular topic but struggles elsewhere, or you’ll find that one of your typically highest attaining students has a blind spot when it comes to nets of 3D shapes. I will now use multiple choice questions every lesson (pupils can vote with their fingers), which means I can detect misconceptions earlier and put steps into place to remedy them.

In terms of differentiation: this will always, always be so important. It is really important that all pupils are supported and challenged in terms of the demands placed upon them, but this does not have to mean five different worksheets.

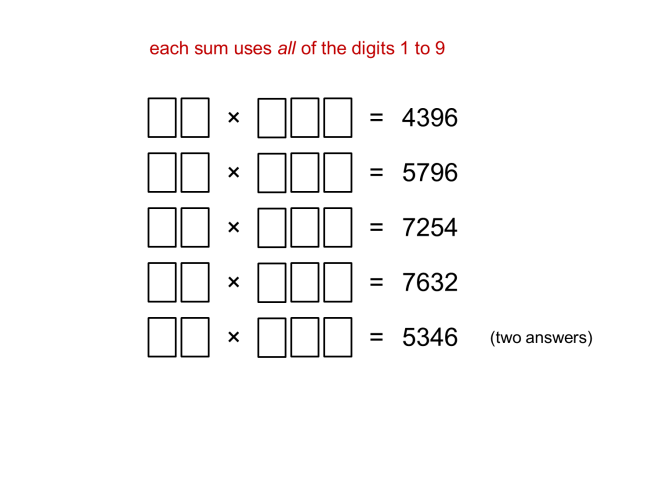

Recently, when students needed to practise multiplying numbers, I gave them this task (by the ever excellent Don Steward).

https://donsteward.blogspot.com/2017/01/consecutive-digits-in-multiplication-sum.html

At a surface level, this doesn’t look particularly interesting. Using it in a classroom, however, was absolutely fascinating. For pupils who are unsure where to begin, you can just tell them to write the numbers in any order in the gaps, multiply them, and see what the product is. You can chat to other pupils about what the units column of what the multiplier and the multiplicand must be: why? How do you know? Is there more than one option? Quite simply, by giving pupils the same task but which will be accessible to most (if not all), you can plan your questions and conversations and prompts much more easily than if all your energy is going into distributing the next worksheet.

At a surface level, this doesn’t look particularly interesting. Using it in a classroom, however, was absolutely fascinating. For pupils who are unsure where to begin, you can just tell them to write the numbers in any order in the gaps, multiply them, and see what the product is. You can chat to other pupils about what the units column of what the multiplier and the multiplicand must be: why? How do you know? Is there more than one option? Quite simply, by giving pupils the same task but which will be accessible to most (if not all), you can plan your questions and conversations and prompts much more easily than if all your energy is going into distributing the next worksheet.

https://donsteward.blogspot.com/2013/12/six-digits.html

A similar activity is this, on adding decimals. Again, this is something that looks almost uninteresting on the surface, and it is certainly something that I wouldn’t have given to my highest attaining pupils in the past, as I would have reasoned that they could already fluent add decimals. When I did use this task, I discovered that even some of the pupils who could add decimals really struggled with reasoning about where various digits must be – but the nature of the task meant that they were forced to think about this while also practising the procedure.

I think probably the biggest cause of my Year 7 lessons being so much more successful than before is this change of approach to resourcing. Don Steward’s blog (https://donsteward.blogspot.com/) is my go to place, as are www.openmiddle.com and www.mathsvenns.com This is not always easy; some topics lend themselves to this style of activity much better than others do. As I say, this is only an overview of what is working for me in the classroom at the moment. I know that there are other people teaching mixed attainment classes with a very different approach to the one that I am using, and so I am really not suggesting that this is the ‘best’ way. I’ll hopefully write something in a few months time about whether this year’s experience is continuing to be quite so positive!

Finding the Equation of Tangents to Circles at a Point

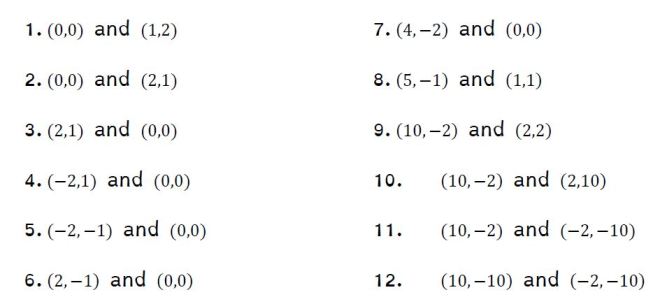

Gradient of a Line

Algebraic LCM

Would recommend reading this excellent post by Jo Morgan for more on the inspiration behind this exercise!

Estimating the Mean from a Grouped Frequency Table

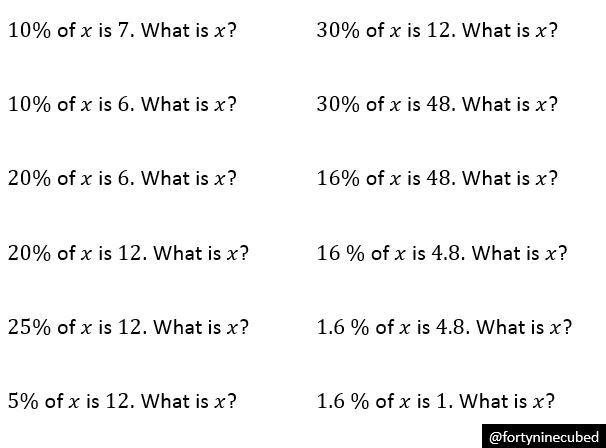

Percentage of Amounts: Reverse

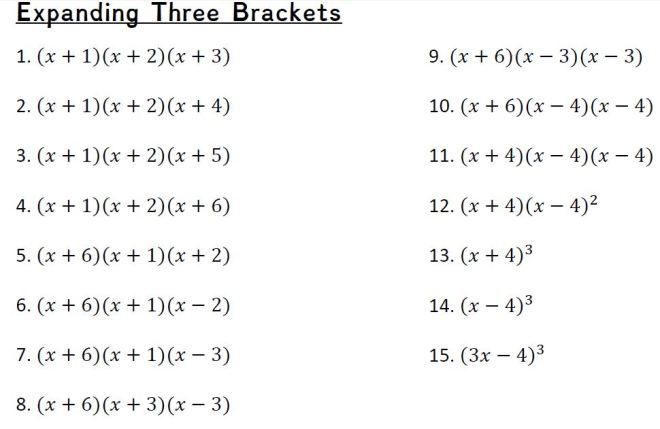

Expanding Three Brackets

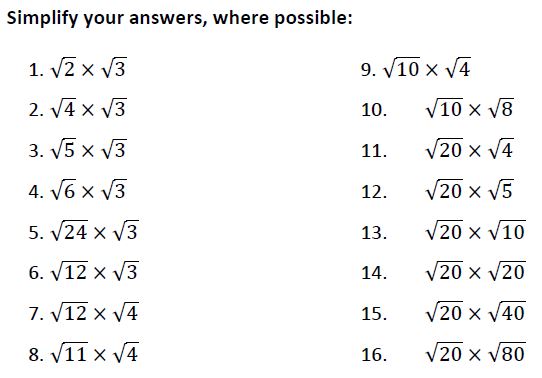

Teaching Surds – Part 3

Having outlined in part 1 (here) and part 2 (here) how I used to approach teaching surds (what a surd is, multiplying, dividing, addition/subtraction, expanding brackets, rationalising the denominator), alongside why these approaches were unsuccessful, I’m now going to share what I do now, and why I think it is contributing to high levels of long-term learning.

When I now begin teaching a class about surds, I will always have assessed that they have certain prerequisites in place: the most important of these is that they are fluent in recognising all squares and square roots up to 225. If a pupil is unable to do this, simplifying surds will become highly inaccessible. My strategy for doing this remains the same as discussed in part 2.

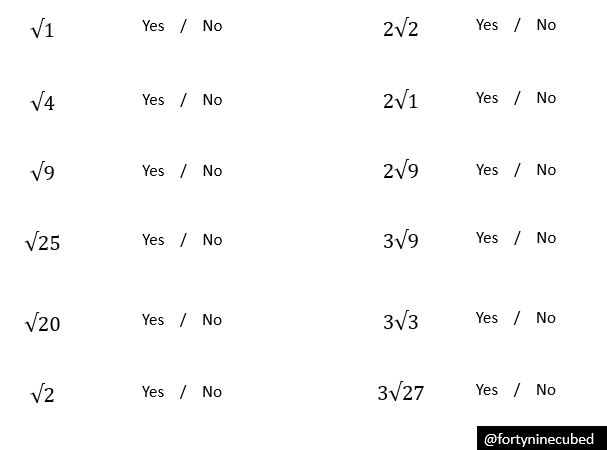

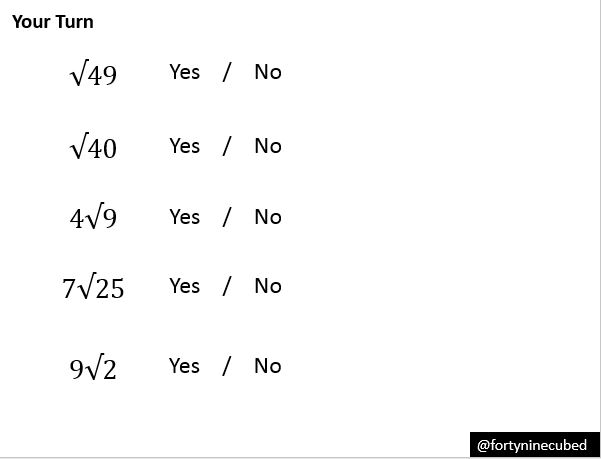

Where my approach starts to change, however, is in that very first lesson. Previously, I would have introduced the topic via Pythagoras’ Theorem, before giving them the official definition of what a surd is. However, although students could repeat this definition, they often lacked a deeper understanding of the concept of a surd. As such, in that first lesson, I present them with this sequence of questions. On a practical level, I display each question on the whiteboard one at a time. I then silently circle the correct answer. I complete the first slide in silence. Pupils, during this time, are entirely silent, and are not writing anything down. They are simply watching, and thinking about what might be going on.

Once this is complete, pupils will complete these 5 practice questions, one at a time, on mini-whiteboards. This will allow me to see who is correctly spotting the rule for what a surd is/is not, alongside who is not. Depending on how this goes, I will make a decision on what to do next. Sometimes, it will make sense to show some more examples; sometimes, where the majority of pupils are confident, we will discuss a definition.

The real advantage of structuring the lesson in this way, is that pupils are often fairly adept at pattern-spotting and identifying rules, and so I’m allowing the opportunity for that to be utilised. By showing both examples and non-examples, pupils will begin to define for themselves: ‘okay, so it’s not a surd when it’s a square number?’. Of course this is not the only definition I want my pupils to have! I will then carefully explain the definition, and we will discuss rational and irrational numbers, but because they already have a concept forming of what a surd is, I have found they are far more able to recall and use this definition.

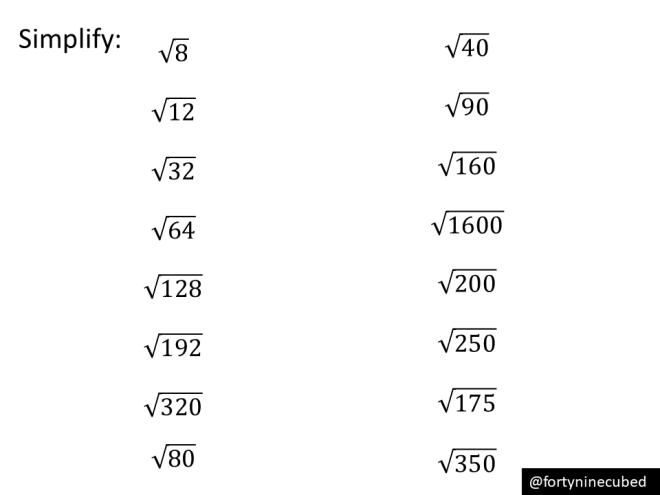

Following on from this, I wanted my pupils to be able to simplify surds. The procedure for this is not something which is likely to be discerned by pupils from viewing examples and non-examples; I have found that is more beneficial to begin with an example-problem pair (please buy and read How I Wish I’d Taught Maths by Craig Barton on this!). I show them an example, on the board, in silence, which pupils watch. After that, I narrate the steps, and pupils then copy it down, before beginning a very similar question independently. If a significant proportion of pupils are struggling to complete these independently, I will complete a second example. Once most pupils are showing that they can replicate the procedure (and initially, this is all I am assessing), they will work through these questions independently.

I really like these questions. The first one is straightforward. The second one is no more difficult, but here I want pupils’ attention to be drawn to the fact that they are both in the form ‘a root 2′. Why is this? How could we have inferred this from the question before carrying out the procedure? This is followed by another question where the answer follows this same pattern. Again, this is useful to discuss with pupils: hang on, root 8 simplifies to 2 root 2, and 32 is 4 times bigger than 8, so shouldn’t it be 8 root 2? Why is that not the case?

(It is worth pointing out at this stage that my pupils (who by now are fairly well practised in reflect, expect, check) found the expectation stage really hard this time round! They kept finding that what they expected to have happened wasn’t happening, hence it was so important to retrospectively expect. Why did this happen? What is happening here?)

Following that, question 4 obviously simplifies to 8. This is only obvious to an expert! With my class, who were all more than able to inform me that 8*8=64 and that the square root of 64 is 8, continued with the procedure that they had just been shown. Upon reaching answers of 8 root 1 or 4 root 4, I then encouraged them to use what they already knew – oh yes, of course that’s 8. This allowed them to see that 8 root 1 and 4 root 4 and 8 are all equivalent, which I would never have previously exposed them to explicitly.

After this, there are three questions in the form 8 root a. Again, this needs to come with follow up questions and discussions. What is it about these surds that means they must simplify in this way? Write me another surd which will simplify in this way. I then want to expose them again to the fact that root 80 is half of root 320. This is curious and surprising to a novice learner of surds! Why is that? What had you expected? Why was this expectation incorrect?

Root 40 still feels like it must be half of root 80, except it isn’t. How can we tell that it isn’t from the simplified forms? This is a really common misconception – I want to draw it out in the earliest stages of instruction, before it becomes embedded and thus harder to correct.

There are then a few questions which allow pupils to refer back to their knowledge of square numbers, and hopefully receive some confirmation that their expectations are correct. This obviously does not always happen. So, root 16 is 4, so root 160 must be 10 root 4! Are you sure? Let’s check. Ah, what mistake have you made? Root 1600 has then been intentionally included – wait, our answer is no longer in surd form – therefore what type of number must 1600 be?

The final few questions give pupils the opportunity to practice and consolidate their understanding.

Now, this set of questions are often completed far more quickly by pupils than a ‘random’ set of simplifying surds questions, because they can use the patterns that they begin to spot to help speed up the procedure. Pupils, throughout, will be encouraged to write down what they are spotting and when they come across a surprising answer – we will discuss these as a class. This has promoted high quality mathematical thinking, reasoning and communication as being really key to success in my classroom: pupils are not just thinking about how to copy a procedure, but they are also thinking about the underlying mathematical structure.

This, however, is most definitely not the end of the story. Pupils will continue to be exposed to ‘simplifying surds’ questions in Do Now activities over the coming lessons, months and year. This opportunity to regularly retrieve knowledge is fundamental if pupils’ long-term memory is going to be affected. They will also meet this topic in other contexts – Pythagoras’ Theorem is the one that springs most readily to mind. However, I don’t just want my pupils to practise simplifying surds – while procedural fluency is key, I want them to think mathematically and so I need to provide them with opportunities to do so.

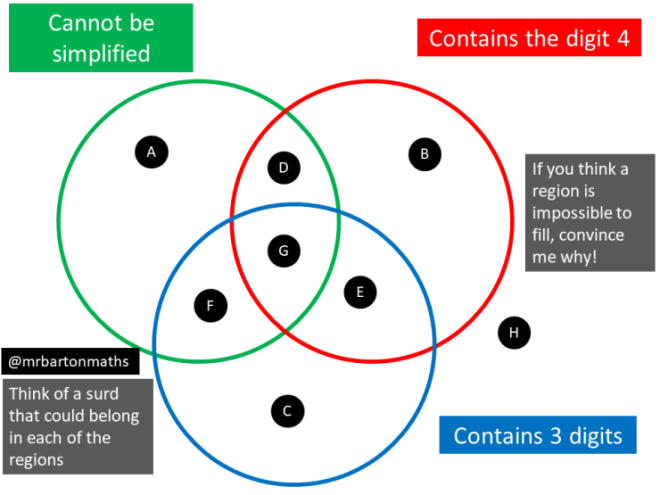

In recent months, I have started making use of Venn Diagrams – primarily from www.mathsvenns.com.

This is a fantastic task. It is open ended and really allows for creativity, and as a tool of assessment, means I can more accurately assess who is happy with the procedure, and who is happy with the underlying structure. I may also use this task when revisiting surds – e.g. with a year 10 or year 11 class who have previously been exposed to the key concepts and procedures. I do not want to use this with pupils before they have the relevant content knowledge in place, or it is likely to cause confusion and leave pupils perceiving surds in a negative way, if they are not given the chance to experience success quickly.

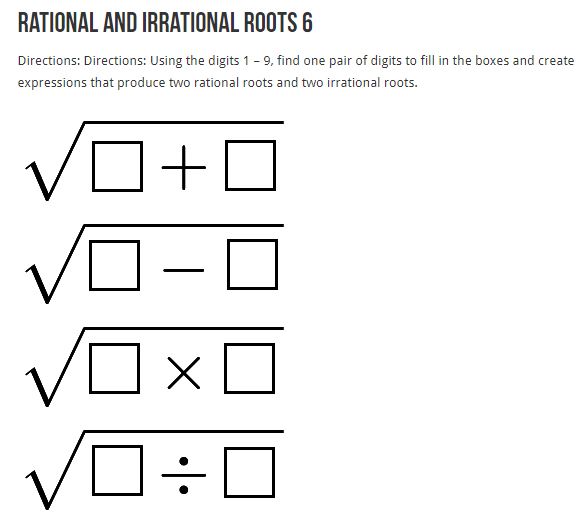

I will also use a variety of problems taken from the fantastic www.openmiddle.com, such as this one below.

Again, this is incredibly powerful. Pupils do not view maths lessons as simply ‘the teacher does examples, we do questions, we get them right or wrong’, but as the opportunity to create and question and conjecture. It is certainly an example of a ‘problem worth solving!’.

Overall, I think this approach to teaching surds has been my best yet. Obviously, it is not perfect and without need of refinement. Some of my pupils still hold misconceptions which I will need to continue to discover and challenge. Some of my pupils will still make ‘silly’ mistakes. Some of my pupils will still forget with alarming regularity. However – on the whole, it feels like we’re getting there.