Yesterday (March 9th 2019) I attended #MathsConf18 – my fourth Maths Conference! This time around, I wasn’t presenting which meant I could attend five workshops, alongside mathematical speed-dating and making hexaflexagons in the Tweet Up at lunchtime. As ever, the whole day was packed with content and I came away (as always) more determined to improve my teaching and with strategies of how to do so! In this post, I will share some initial reflections on the workshops I attended.

Workshop 1

My first workshop was on Managing Workload from @MrEdWatson – a Head of Maths from Bristol. While I would generally describe my workload as being ‘manageable’, this is something that I have to work hard to manage and typically involves working longer term-time hours than is probably optimal. As such, I was keen to leave with some strategies to put into place to help here.

Ed encouraged us to think about a typical teaching day, and place the tasks that we complete into the below table (taken from the work of Stephen Covey).

During a typical day, I would describe most of the tasks that I complete as being both urgent and important (quadrant 1). This, though, often leads to a feeling of ‘fire-fighting’ and higher stress levels about the tasks to be completed – it is better for productivity if we are working in quadrant 2 (important, not urgent) as much as possible.

Ed also spoke about how it is really easy to spend a lot of our time being busy, but not productive. This really resonated with me! It is quite easy to make it to the end of a long day at work and still feel as though you have failed to accomplish what you set out to do. A possible strategy to help rectify this is to write a ‘to-do’ list of tasks for the next day the next evening; while this sounds obvious, it isn’t something I do routinely which means I end up completing tasks ‘as and when’, rather than scheduling my time most effectively. We also looked at how all tasks expand to fill the time you have available – if you have 3 hours to plan a lesson, it will take you 3 hours. If you have 10 minutes, it will take 10 minutes. Again, this is something I want to work on! While I am certainly not a perfectionist, I am definitely guilty of spending hours on tasks which will not have a significant impact on student learning, simply because I have the time available. Ed really stressed that time is precious – to be as impactful as possible, we need to be ruthless with how we allocate our time.

There was so much food for thought in this session alongside some potentially controversial points raised (textbooks – yes or no?) and Ed was a fantastic speaker – I came away with things that I want to try immediately; we will see how that goes!

Workshop 2

I finally managed to attend a workshop by Naveen Rizvi (@naveenfrizvi) – after the past two conferences where I was presenting at the same time as her, it was such a wonderful opportunity to see what she’s been working on!

The focus of Naveen’s presentation was on atomisation (that is, breaking down a task/skill/procedure into all of its sub-skills/tasks), with a specific focus on teaching angles in parallel lines. I’ve been working hard over the last year to break down content as much as possible when I am teaching, but I always find this much harder when trying to teach geometrical concepts, so I was really keen to find out how Naveen had done this.

One thing Naveen said was that most typical exercises for students to practice angles in parallel lines were either really easy, or really hard, without much for the ‘in-between’ stage. This is something that I have definitely found in my experience – most students can find pairs of alternate, corresponding or co-interior angles where that is the only skill required, but then struggle to access multi-step ‘exam-style’ questions. Naveen took us through a series of examples/questions that she had developed. It was fascinating to see how by focusing on changing just one thing (for example, including an extra transversal) each time, her students would be able to be successful at the most challenging mathematics. Throughout her presentation, this emphasis that Naveen placed on ‘success for all’ was apparent – she stressed how by spending time on planning carefully chosen examples and scripting explanations, it meant that all her students would achieve success, rather than just a handful of ‘high-attainers’.

The other thing Naveen said which resonated hugely for me was that by ‘breaking down a topic into its sub-tasks, a teacher can identify 100% of the domain of knowledge’. When teaching any topic, it is easy enough to look at a scheme of work, teach what you believe to be the required content, and yet later testing reveals that your students have significant gaps. For example, when teaching ‘angles in parallel lines’ previously, I may well have forgotten to include any instruction related to isosceles triangles and angles in parallel lines, or parallel lines involving multiple transversals. I almost certainly would have failed to include multiple orientations. The amount of thought that Naveen puts into how a topic should be taught to ensure everything followed in a logical order and didn’t lead to further misconceptions was remarkable. I’m not sure when I’m next teaching this topic but I already cannot wait!

Workshop 3

For workshop 3, I attended Andrew Taylor’s (@AQAMaths) session on old exam questions and papers. Having only sat my Mathematics GCSE in 2009 and having started teaching in 2015, I wasn’t that aware of how the qualification had changed over time, so I was excited to find out.

Andrew started with a couple of non-calculator arithmetic questions for us to try (I cannot remember at all which year these were taken from!) – it was very apparent how the level of challenge for arithmetic in 2019 is certainly not what it once was. Several people commented that even their highest attaining year 11 students would struggle with what was required.

Andrew shared a number of examples from previous Mathematics exam papers with us; it was so interesting to see how certain types of question haven’t changed much at all in the last fifty years whereas others would be virtually unrecognisable (my favourite was was the one featuring Welsh towns and trigonometry!) to a student sitting the paper today. I also had no idea how much choice there used to be in Mathematics papers/qualifications. The University of London’s O Level in 1957 featured three compulsory 2.5 hour long papers on Arithmetic and Trigonometry, Algebra and Geometry, alongside an optional paper (which could be on the History of Mathematics!). It certainly put into perspective the three ninety minute papers that our students sit today.

Again – this was a really fascinating session! Andrew gave us an old O Level paper which I cannot wait to show my students next week.

Workshop 4

After lunch and the mathematical tweet-up, I attended Jo Morgan’s (@mathsjem) session on Topics In Depth: Unit Conversions. Now, I cannot pretend to be particularly thrilled when I see that I have unit conversions coming up on a Scheme of Work, so I was hopeful that I would come away feeling at least slightly more inspired.

Jo started with showing us the KS2 National Curriculum requirements for working with measures and different unit conversions – she made the point that many of our Year 7s will be fairly adept at converting between different metric measures (and solving problems involving this skill) but that this often seems to be lost somewhere between Year 7 and Year 11. This is something that has definitely been true in my experience; I have taught numerous Year 11 students who cannot remember the number of centimetres in a metre or grams in a kilogram.

Jo shared with us some of her research about the etymology of unit prefixes (kilo-, deci- centi-, milli-, etc.). While this is something that I do mention to my classes, I think I tend to skip over it in favour of practice. I hadn’t known that bigger units (kilo, mega, giga etc.) all come from Greek, whereas smaller units (deci, centi, milli etc.) all come from Latin – while not necessarily ‘useful’ knowledge, definitely something interesting that I want to share with classes in future!

Jo shared with us a number of different ways that we can teach students to convert between different units; conversations with the people I was sat with suggested that we generally favour a ratio table or a common sense/reasoning approach. I’ve recently loved using proportionality diagrams for all sorts of ratio/proportion problems, so I was really pleased to see that this excellent post by Don Steward was mentioned.

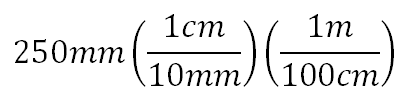

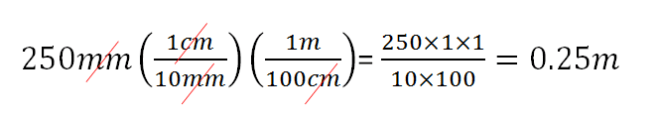

The most fascinating part was Jo teaching us a new method for unit conversions; that of ‘last unit standing’. I have still not decided how I feel about this method or if it is something I will ever use in the classroom – but it was such a delight to see something completely new! Here is how it would work for a relatively simple problem:

Convert 250mm into metres.

It also works for compound measures! For more on this, I would recommend look at Jo’s slides which are available here. I cannot stress enough – even if I make the decision to never use this with students, I love knowing that it exists and that it gives me another tool at my disposal.

Workshop 5

For my final workshop of the day, I went to see Kris Boulton (@kris_boulton) presenting on solving equations. It is always a real pleasure to see Kris present because it is so clear how much thought has gone into everything that he shares. Having spent a week at King Solomon Academy when Kris was teaching there in 2016, I know first-hand how really carefully sequenced instruction leads to remarkable outcomes, so I am always keen to learn more about how he approaches his planning.

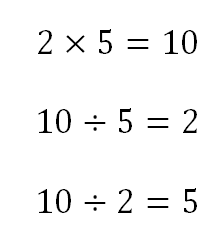

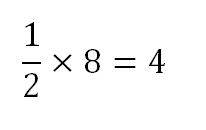

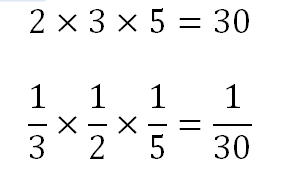

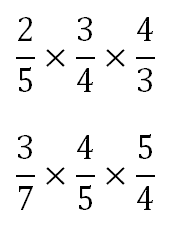

Kris shared with us 17 processes that students need to be fluent with to be successful at solving one-step equations. Something I really noticed from this was how much important Kris would place on what the equals sign means, alongside looking at statements of the form:

7+3=6+4

before beginning the process of solving. While I have been developing this over the last few years, I am definitely guilty of choosing:

x+4=9

as the starting point, when to do so is presuming an overwhelming amount of prior knowledge that my students wouldn’t have access to.

The method Kris shared with us for solving equations is 4 steps:

- Decision-make

- Break

- Repair

- Simplify

Usefully, by identifying these four steps as exactly what needs to be done to solve any linear equations, we don’t have to expect students to complete all four steps from the very beginning. For example, it may well be beneficial to spend a period of time on just the ‘break’ stage, before moving to looking at ‘repairing’. I was also particularly taken by the use of the words ‘break’ and ‘repair’ – typically, I have stressed ‘having to do the same to both sides’ when teaching equations, but I am not sure the extent to which students actually understand what I mean or why they are doing it. There was something intuitive about how Kris introduced breaking and repairing, which I am really keen to try out.

Now, it is obvious that to teaching solving equations to a class using this method is going to take far more time than I would have spent on this previously. However – whenever I have taught this previously (to any class at any stage of their mathematical journey), they have had to be retaught various parts at various points. Ultimately, it will be better to invest more time from the beginning than to have to reteach and fix and correct many many times over. I left with so much to think about and ideas to try out.

Finally: I cannot thank Mark (@EmathsUK) and the whole La Salle Education (@lasalleed) team enough for all they do for Maths teachers alongside raising money for Macmillan Cancer Support. The whole #MathsConf movement has been such a massive support for me in terms of making connections with other teachers and improving my own practice. If you’ve not attended before, make sure you book for Sheffield in June – even if you are nervous about coming alone (as I was, the first time!) you will meet the best people and have the best CPD. See you there!

Now, the first time I tried using a Venn diagram, it did not go well. I think I had been too vague about what was expected of them, and so they didn’t really know what I was getting them to aim at – my suggestions of ‘make up your own example!’ was not received well, as they had such a focus on being ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ that the message was lost. As such, I adapted this task in the smallest way: I gave them three questions to place into the Venn diagram.

Now, the first time I tried using a Venn diagram, it did not go well. I think I had been too vague about what was expected of them, and so they didn’t really know what I was getting them to aim at – my suggestions of ‘make up your own example!’ was not received well, as they had such a focus on being ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ that the message was lost. As such, I adapted this task in the smallest way: I gave them three questions to place into the Venn diagram.